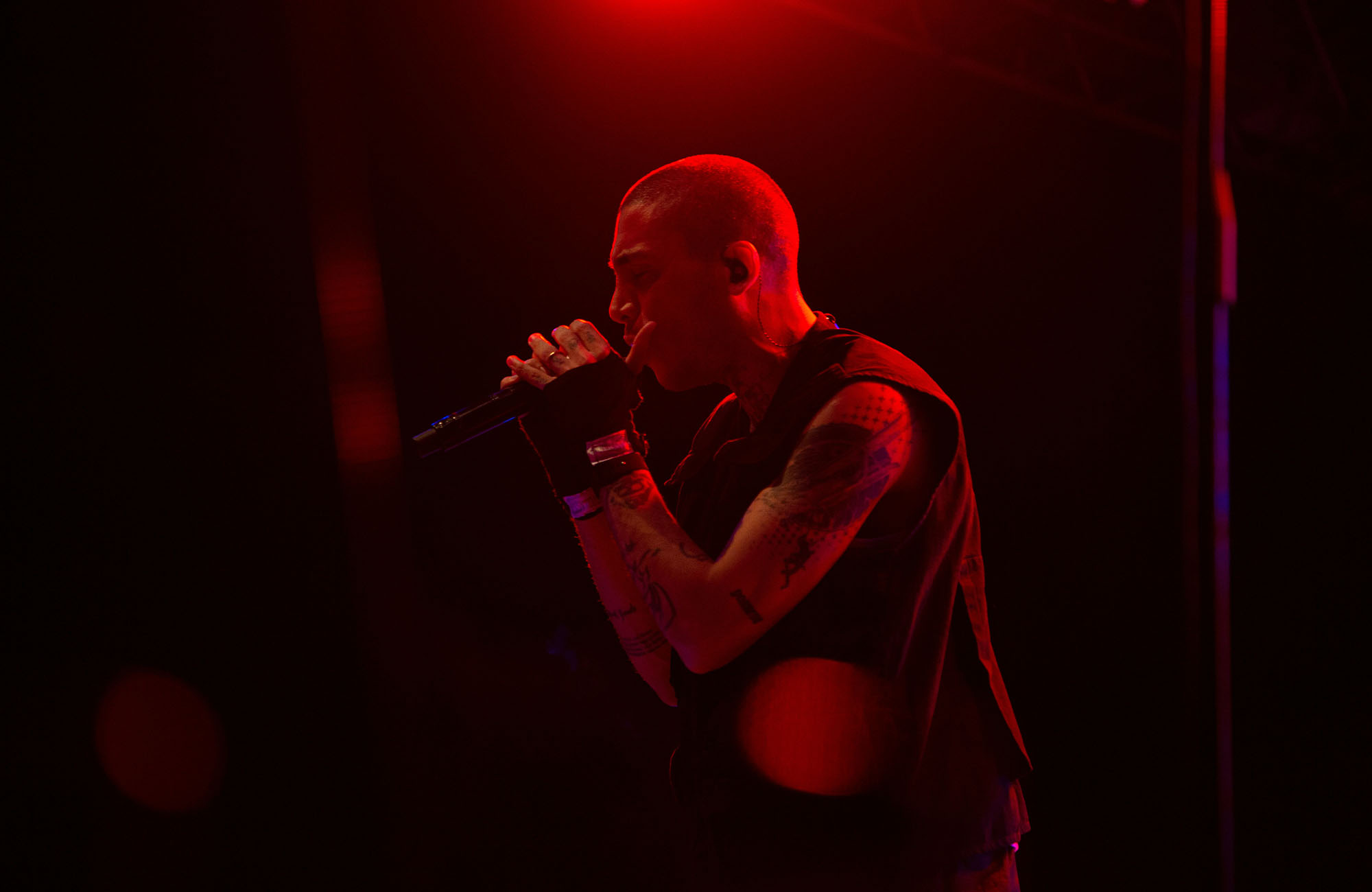

Flow Experiments: Simple Exercises to Discover New Patterns Over Type Beats

Every rapper hits that point where everything starts to sound the same. You open a beat, you nod your head, and without thinking your mouth jumps into the exact same cadence you used on the last three songs. It is comfortable, but it is also boring. At some point, your flow stops growing, and even if your lyrics get better, the patterns underneath them feel copy–pasted.

The good news is that flow is not magic. It is a combination of rhythm, syllables, breathing and confidence. That means you can train it. Just like a basketball player runs drills, a rapper can run flow experiments. This article gives you a set of simple exercises you can use to break out of your usual patterns and discover new ones over type beats you already love.

Why Your Flow Keeps Sounding the Same

Most artists default to the same flow because the brain loves shortcuts. Once it finds a rhythm that “works,” it will repeat it automatically. You may not notice it, but you probably have a default number of syllables per bar, a favorite way of entering the first line, and a certain spot in the bar where you always land your punchlines. You also probably pick similar beats over and over, which reinforces the same pocket.

The goal is not to throw all of that away. Your natural flow is part of your identity. The goal is to stretch it. When you deliberately push your timing, your syllable count and your starting points, you teach your ear and tongue to be more flexible. That flexibility is what separates a one-dimensional rapper from someone who can adapt to almost any beat.

Setting Up a Flow Practice Session

Before you start experimenting, it helps to set up a simple practice environment. Pick a few beats in advance instead of hunting while you practice. It is useful to choose two or three type beats with clearly different tempos and moods: for example, a laid-back, slightly slower track, a mid-tempo bounce, and a more intense, faster instrumental. If you use a catalog like the one on Tellingbeatzz, you can quickly grab a mix of hip-hop and rap beats with different energies from the Beats & Instrumentals section and drop them into a playlist.

Decide before you start how long you want to practice. Even fifteen focused minutes can be enough. The key is that in this time, you are not trying to write a perfect song. You are here to play with rhythm. If you stumble, laugh it off and keep going. Flow training is messy by design.

Exercise 1 – One Verse, Many Tempos

The first experiment is simple: take one written verse and use it as a test object. Choose a verse you already know by heart. Play a beat that is close to the original tempo of that verse and rap it normally. Then switch to a slightly slower beat and deliver the exact same verse again, this time consciously stretching certain words, holding out syllables and leaving bigger gaps for breathing.

After that, jump to a faster beat. Now you have to tighten your timing. You might need to clip certain words or roll them together more smoothly. The point of this exercise is not to make the verse “fit perfectly” on every beat. The point is to teach your body that the same group of words can live comfortably inside different pockets. Over time, you stop thinking of your flow as fused to one tempo, and you become more fearless about switching energy levels.

Exercise 2 – Syllable Limits Per Bar

This experiment trains your sense of density. Pick a beat and decide on a strict rule for a few minutes. For example, you might decide that for the next eight bars, you will only allow yourself around six to eight syllables in each bar. That forces you to leave space, to choose fewer words, and to lean more on tone and swing than on speed.

Once that feels natural, flip the rule. Now you aim for a much higher density, maybe twelve to sixteen syllables per bar, while still staying clear and on beat. Do not worry if it sounds messy at first. You are stretching your internal metronome. After a few rounds of switching between sparse and dense bars, your normal flow will start to land somewhere in the middle with more control. You will be able to speed up or slow down within a verse without losing the groove.

Exercise 3 – Off-Beat Entries and Late Landings

Most rappers always start their lines in the same place, usually right on the one or just before it. This makes your flow predictable. To break that habit, run an experiment where you deliberately come in late or early. Start by counting the beat out loud: one, two, three, four. Then pick a spot you are not used to, such as the “and” between counts.

Try beginning your line slightly after the one, almost as if you are sliding into the bar a little late. It will feel wrong at first, but if you keep going, you will notice new syncopations appearing. Then try the opposite and jump in slightly ahead of the beat, letting the drums catch up to you. The goal is not to rap off beat, but to understand that there are many possible entry points. Once your body understands that, you will naturally start to place words in more interesting positions inside the bar.

Exercise 4 – Vowel and Consonant Drills

Flow is not only rhythm; it is also the sound of the syllables you stack together. Certain combinations of vowels and consonants roll off the tongue faster or slower. To feel that, pick a simple pattern of sounds and loop it over a beat for a minute or two. For example, choose a consonant like “B” or “K” and a few vowel shapes, then improvise nonsense phrases that focus on those sounds. You might mumble something like “ba-ba-bay-bu” or “ka-kee-ko” in different rhythmic shapes.

It will sound ridiculous, but what you are really doing is training your tongue to move in new ways at different speeds. After a few minutes of this, switch to real words and notice how much looser your mouth feels. Fast patterns that used to trip you up suddenly feel more natural because you have rehearsed similar movements in a low-pressure way.

Exercise 5 – Hook Flow Versus Verse Flow

Many rappers use almost the same flow in their verses and hooks, which makes the song feel flat. This exercise is about exaggerating the difference. Pick a beat you could imagine using for a real song. Start by improvising or writing a simple hook. Keep the rhythm of that hook extremely clear and repetitive, as if you want a crowd to be able to chant it back to you. Record or memorize it.

Now, when you move into the verse, make it a rule that your flow must change. If your hook is slow and bouncy, let your verse be more rapid and intricate. If your hook is packed and aggressive, let your verse breathe more and leave gaps for emphasis. The important thing is that you keep referring back to the hook flow in your head, so you can feel the contrast. After practicing this on multiple beats, you will naturally begin to shape songs where the hook and verse feel like different characters instead of the same pattern repeated on a loop.

Exercise 6 – Borrowing Pockets From Your Favorite Artists

You can also learn a lot by studying flows you admire. Pick one artist at a time and focus only on their rhythm, not their exact lyrics. For example, you might listen to an NF-inspired type beat track and pay attention to how tightly he stacks syllables at certain points and how much space he leaves before explosive moments. Or you might study an Eminem-style beat and notice how he plays with internal rhymes and stress patterns inside each bar.

Once you have a feel for one of those pockets, put on a different beat and try to freestyle using that same kind of rhythm with your own words. You are not trying to copy their style forever, just to walk in their shoes briefly. After you do this with several artists, your own flow will start to inherit little tricks from each of them, and you will discover combinations that feel unique to you.

Turning Experiments Into Real Songs

Flow drills are powerful, but they only matter if they show up in your actual music. After a practice session, do not just close your notebook and walk away. While the new patterns are still fresh in your body, pick one beat you really like and commit to writing a full hook and verse. The rule is that somewhere in that song, you must use at least one of the experiments you just did.

Maybe you decide that the verse will start a little later in the bar than you are used to. Maybe you keep the first half of the verse sparse and then suddenly increase the density in the second half. Maybe you use a hook that is extremely simple and repetitive on purpose, because you have finally felt the power of contrast. By consciously planting one experiment inside a real track, you start turning practice into instinct.

Building a Weekly Flow Training Routine

To really see progress, it helps to think of flow experiments as a regular workout instead of a one-time trick. You might decide that two or three times a week, you will spend twenty minutes on exercises before you start writing songs. Each session can focus on a different experiment, or you can rotate through several quickly. Over time, you will notice that you are less afraid of unusual beats and more willing to take risks.

If you want to make it more fun, you can create a small playlist of instrumentals from a trusted source like Tellingbeatzz, mixing different moods and energies so every session feels fresh. Some days you might work on tight, intense patterns over darker production, other days you might explore looser, more melodic flows over dreamy or laid-back beats. The important part is that you keep showing up and giving yourself permission to sound weird while you learn.

When you treat your flow like a muscle to be trained instead of a fixed talent, you unlock a new level of control. The next time someone sends you a beat that feels slightly outside your comfort zone, you will not panic or fall back into the same old cadence. You will have a toolbox of experiments ready to go, and the confidence to find a new pocket that fits both you and the instrumental.

Browse Beats & Instrumentals

Check out my extensive catalog of more than 500 custom-made beats and instrumentals, available for free download or licensing.

No Comments